A modest invention that prevented celluloid from tearing helped make modern cinema. An Object Lesson.

In the late 19th century, filmmakers had a problem they couldn’t have anticipated: how to make a film that lasted more than a few seconds without tearing. In film’s earliest days, this had hardly been an issue. Film was a novelty, and brevity was part of the appeal. It offered spectacle, like glimpses of Annie Oakley shooting or prizefighters competing in the ring—sights people would never be able to see in person.

But after the initial shock wore off, the public wanted something more. They began to understand what it was film had to offer: The seeds of fiction were planted in these short, performed events.

Before film was art, it was machinery. It took years for film to get the kind of legal protection that the other, more prestigious arts enjoyed. In the early days, it was technology, protectable only by patent. As a result, film, as a product, was strange and vulnerable, subject to duping, sabotage, and all kinds of strange patent traps set by Thomas Edison to keep independent filmmakers from gaining power.

Edison hadn’t invented the technology behind the moving picture. In the 1880s, the photographer Edward Muybridge created a sequence of images that, if viewed together in rapid succession, simulated movement. The first functioning camera and projector likewise didn’t come from Edison, but the Lumière Brothers. Edison refined and commercialized their invention, turning film’s focus toward storytelling and away from documentary. He also thought globally. By the mid-1900s anyone with a camera could produce—or just copy—films. Distributing them was another matter. That, Edison knew, was where the money was.

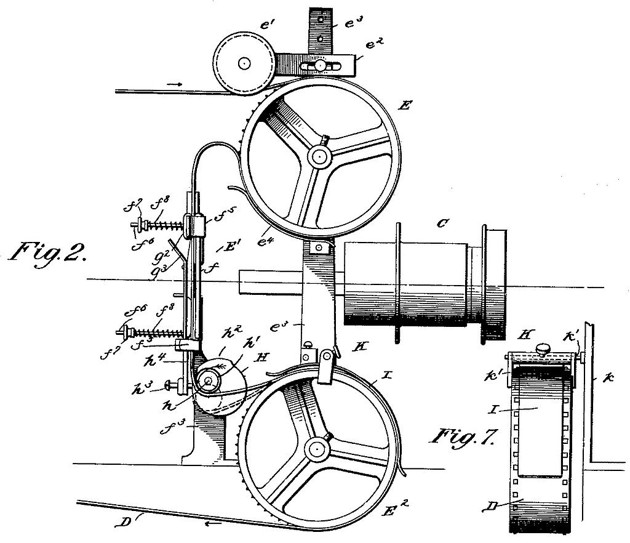

Enter the Lathams—a father, Major Woodville (a Confederate) and his hard-living sons Otway and Gray. In their quest to film a boxing match and screen it for a paying audience, they invented the Latham Loop, a way of pulling film through the threading device of the camera gently enough not to tear the sprockets—and more importantly, a device that enabled the film to gently spool over from back to front, allowing for longer films. Their projector was called the Eidoloscope, and it had the instant advantage over Edison’s competing product.

From 1891 onward, Edison had tried to corner the new, lucrative market for films. By 1894, he turned to the Lathams, who had asked for financial help in creating a device allowing for longer pictures, with the aim of projecting filmed boxing matches for admission. In 1895, they were successful. In May of that year, as Dan Streible documents in his book Fight Pictures: Boxing and Early Cinema, the Lathams screened a fight between “Young Griffo” and Charles Barnett in New York City in a widescreen format.

The Lathams continued to screen spectacles for the public, until the money ran out. Edison’s protégé, W.K.L. Dickson, distanced himself from both the Lathams and Edison in 1895, just in time to form his own company. He’d call it Mutoscope, soon to be known as Biograph, the studio that would produce some of the most influential narrative films of the early century, among them Birth of a Nation in 1913.

Edison didn’t like competition. His nickelodeons, or “peep shows,” were all the rage in the early aughts, before the problems of screening films for large audiences had been fixed to anyone’s satisfaction. But when the competition started heating up, Edison turned to his patents to squeeze the market. He’d intimidated filmmakers out of competing against him in previous years, so much so that there were more French films on American screens from 1906 to 1909 than American ones.

Edison went further in 1908, by creating the Motion Picture Patents Company, or Film Trust. By joining forces with the other big studios of the day (Dickson’s Biograph excluded) he’d hoped to exert his power against burgeoning independent filmmakers by patenting every part of the film camera down to the sprocket holes. Independent filmmakers didn’t have much in the way of legal recourse against the Edison machine. The Sherman Antitrust Act had passed in 1890, before the earliest films had an audience. Copyright laws wouldn’t take motion pictures under protection until 1912.

But Edison had forgotten something: Dickson’s long-held grudge. Dickson side-swiped Edison, coming up against him with his ownership of the Latham Loop, which Edison, in his rush to power, had somehow forgotten about.

By 1908, the Loop was integral to any film projector and camera—as it remains today. It had been patented by 1902 by Woodville Latham, only to be then sold on the cheap to Ansco (Anthony and Scoville Co.) when the Lathams were running low on money. In 1908, Dickson and Biograph bought up the patent and used it to beat Edison and the MPPC at its own game.

It was a bold move in an increasingly cutthroat industry on the verge of incredible growth—and it meant war.

* * *

Along with the loop patent, Dickson had also devised a “friction feed,” the answer to Edison’s patented sprocket holes. Dickson’s camera punched its own holes as the film wove through the machine. With these innovations, Dickson had proved a match for Edison. They combined forces, forming a powerful conglomerate.

Afterward, the Latham Loop became a pawn in Edison’s battle against independents. In conversation with the author and director Peter Bogdanovich, whose 1971 book Who the Devil Made recorded conversations with early filmmakers, the director Allan Dwan said that it was akin to “selling an automobile and not letting anybody else drive it because you have a patent on putting your foot on the pedal.” Non-compliant competitors found themselves subject to intimidation. When these companies moved out West, according to Dwan, Edison sent gangsters across the country to follow them.

“They always shot at the cameras,” recalled Dwan. “Most companies only had one. Sometimes they’d wait until a fellow was cleaning the camera … and take a shot at it. Anything to destroy it.”

Even when it didn’t work, Edison’s toughs could take as well as they could give. “In La Mesa,” Dwan told Bogdanovich, “a rough-looking character got off the train and looked me up. He said he was sent out to make sure me and my company got out of there and quit making pictures. We took a walk up the road to talk it over. I wanted to get him far enough out of town to see if I couldn’t beat his brains out.” The pair competed at shooting cans off a rock. Dwan bested him, and the tough left town that day. Bound to become the art of the masses, film couldn’t be controlled with the same ruthlessness as big business.

* * *

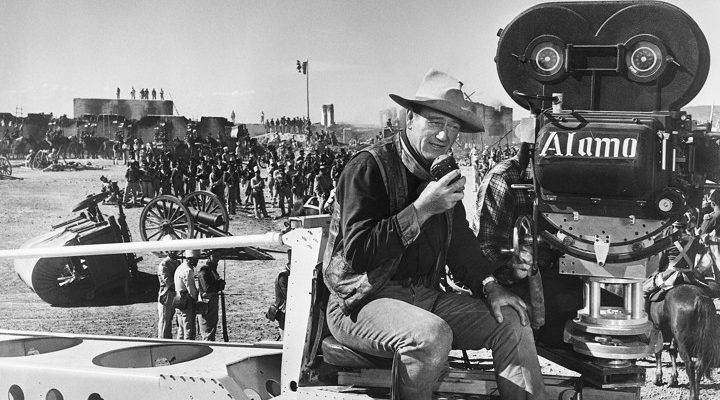

Fights like those, Dwan recalls, didn’t just set the context for filmmaking, they also provided the setting for the films that would be made in the new climate of the West. Once the independents got used to defending their territory in the West, they found that the setting was conducive to filmmaking on a grand scale. Hollywood was a wilderness at the time—a suburb of Los Angeles that counted on the larger city for its water supply. The town’s climate was ideal for filmmaking: dry heat, open spaces, and consistent, beautiful weather. In the early 20th century, a renegade culture still drove filmmaking, one germane to the West.

The lawless wilderness stuck with film, helping invent one of its earliest and most enduring genres: the Western. By 1909, Westerns (shot in the East) already dominated the big screen. Their appeal would only grow as the industry grew, inside the very climate that had inspired the genres’ tales of greed and lawlessness.

D.W. Griffith was one of the first filmmakers to capitalize upon the myth of West artistically. The first film to be shot completely on location was Griffith’s In Old California, which he made for Biograph in 1910. To Griffith, the West still contained the mythos of American naturalism, first born in the works of Jack London and Frank Norris. For a filmmaker defined early on by his attention to atmosphere, nature, and sunlit outdoor scenes, centering his company in California was obvious.

In a different time, Griffith could have laid claim to intellectual property and made a fortune. After all, he’d invented the close-up. Instead he ended up drunk and dissipated, abandoned by the art form to which he gave life. Griffith’s taste in subject matter, too, ended up betraying him. He’d made films that brought the art form into a kind of maturity, but whose politics left them stuck, of necessity, in the past. His Birth of a Nation remains his defining work—at once a great achievement and shameful embarrassment.

By 1909, a year into the patent wars, Griffith would produce and release A Corner in Wheat the first film to use a narrative technique completely unique to the screen: cutting between scenes not just to advance the story, but to make an intellectual point. “Wheat” was about a tycoon whose greed causes him to die at the hands of his own unfeeling, mechanical creation. In the new decade, Biograph’s influence would fall away, and so would Edison’s, as more and more filmmakers and companies set up in the West. By the 1920s, Hollywood had become something close to what we know it as today—the capital of film production, a place where dreams were shot, cut, and processed. A place into which went blood and sweat, and out of which came the glamorous mandates of a budding American culture, in almost equal measure.

Leave a Reply